This week marks 250 years since James Watt’s momentous journey southwards to Birmingham, as he left Scotland to continue the development of his most famous invention – the condensing steam engine – in a new working relationship with the energetic businessman Matthew Boulton. The partnership of Boulton and Watt would eventually lead to great commercial success and international fame, and became one of the most legendary names in the history of global engineering and technology.

Watt had tested prototype versions of the engine in the grounds of Kinneil House at various times during the years 1765-73, in experiments conducted jointly with Dr John Roebuck, the then tenant of the house. It was Roebuck and Watt who together took out the celebrated patent for the invention in 1769, at around the same time that Roebuck built the James Watt Cottage as a workshop for Watt. It was the setting for the later tests to be secretly carried out.

Unfortunately, Roebuck suffered increasing financial difficulties and, thanks also to a banking collapse in 1772, became bankrupt in 1773. “My heart bleeds for his situation“, Watt wrote sympathetically later that year.

In May 1773, Watt dismantled the Kinneil engine, writing from Kinneil on 20 May 1773 to his Scottish friend Dr William Small who had become an associate of Boulton’s in Birmingham:

“On Monday last I concluded bargains with Dr R[oebuck] for his property in the engine… As I found the engine at Kinneil perishing, and as it is from circumstances highly improper that it should continue there longer, and I have nowhere else to put it, I have this week taken it in pieces and packed up the iron works, cylinder, and pump, ready to be shipped to London in its way to Birmingham, as the only place where the experiments can be completed with propriety. I suppose the whole will not weigh above four tons. I have left the whole wood-work until we see what we are to do, conceiving it not to be worth carriage…”.

In June or July 1773, the crates were shipped south, as related in Watt’s letter to Small of 25 July:

“The engine was sent off for London, in the Duchess of Hamilton*… to be heard of at Hawley’s wharf, in boxes No 5 to 17, marked ‘M.B., Birmingham’. If you do not choose to have the engine to Birmingham, as I think you ought, I must beg you will cause care to be taken of it upon my account till I see you“.

[* – The ship’s name is a nice co-incidence in the light of Kinneil’s ownership by the Duke of Hamilton! Presumably it sailed, and the goods were loaded, from the port at Bo’ness.]

In September 1773, Watt suffered the tragic early death of his beloved wife Peggy, and by December, he appears to have been in a state of despondency and uncertainty, confessing in another letter from his home in Glasgow on 11 December:

“I am heart-sick of this country; I am indolent to excess, and what alarms me most, I grow the longer the stupider. My memory fails me so as often totally to forget occurrences of no very ancient dates. I see myself condemned to a life of business; nothing can be more disagreeable to me; I tremble when I hear the name of a man I have any transactions to settle with… The engineering business is not a vigorous plant here; we are in general very poorly paid… There are also many disagreeable circumstances I cannot write; in short I must, as far as I can see, change my abode. There are two things which occur to me, either to try England, or endeavour to get some lucrative place abroad; but I doubt my interest for the latter…”

By April 1774, he was more or less settled on his plan to move to Birmingham, writing again to Small from Glasgow on 9 April 1774:

“I begin now to see daylight through the affairs that have detained me so long, and think of setting out for you in a fortnight at furthest. I am monstrously plagued with my headaches, and not a little with unprofitable business. I don’t mean my own whims; these I never work at when I can do any other thing; but I have got too many acquaintances”.

He was, however, still in Glasgow on 6 May:

“I have persuaded my friend Dr [James] Hutton, the famous fossil philosopher, to make the jaunt with me, and there are some hopes of Dr [Joseph] Black’s coming also…”.

According to Watt’s most recent biographer, it was on 20 May 1774 that he finally set off for his journey south. It is a telling sign of his friendship and respect for Roebuck that he first stopped off at Kinneil to bid his farewells, and then Edinburgh. By 31 May he was approaching Birmingham, and the beginning of a new life.

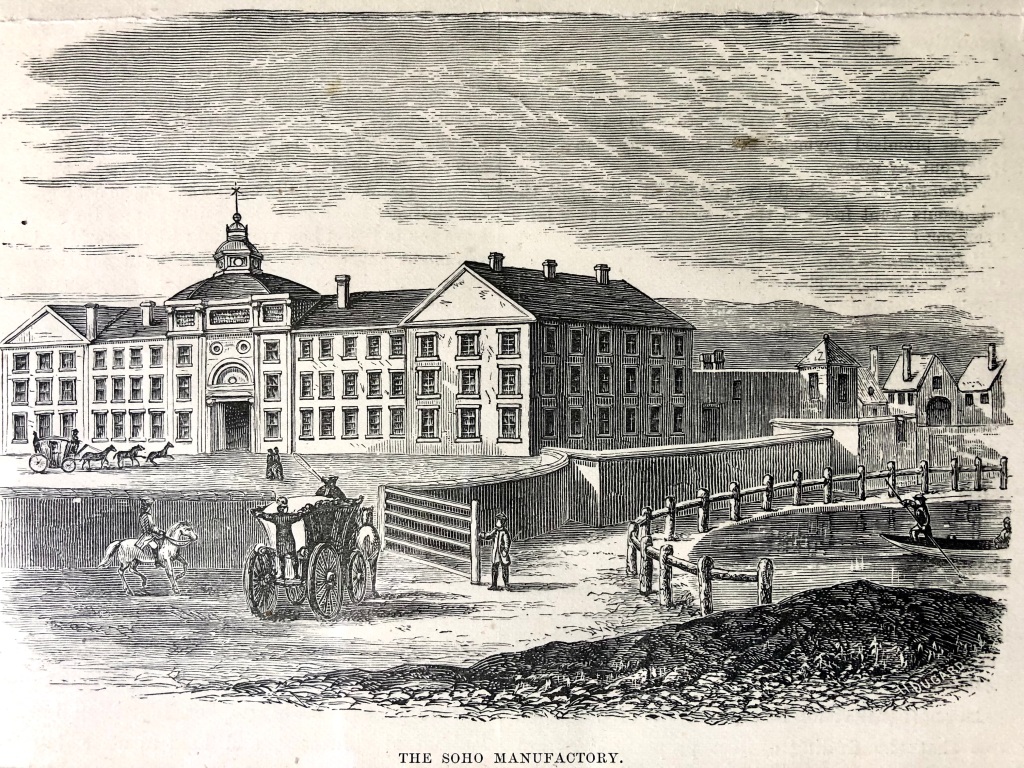

The Kinneil engine was re-assembled in Birmingham and was at last made to run smoothly. It became the first James Watt steam engine to be successfully put to use in an industrial context, being used to pump water around Boulton’s Soho Manufactory. On 11 December 1774, he wrote from Birmingham to his father:

“The business I am here about has turned out rather successful, that is to say, that the fire-engine I invented is now going, and answers much better than any other which has yet been made; and I expect that the engine will be very beneficial to me“.

Extracts from James Watt’s fascinating correspondence are quoted from The Origin and Progress of the Mechanical Inventions of James Watt, by James Patrick Muirhead, 1854. The notes and correspondence from James Watt’s Kinneil period were placed on the UNESCO Memory of the World register in 2020 – the documentary equivalent of World Heritage Sites. They are held along with the rest of the Boulton and Watt archives in the Library of Birmingham, which is also marking this week’s 250th anniversary in their own separate blog post today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.